This post is the second of two in response to CNN’s “Inside Man,” my first was posted yesterday. I decided to make this one separate because while the reflection was sparked from a few scenes in that program it goes beyond that one hour and that one particular school.

In this Inside Man episode, Morgan Spurlock visited a school in Finland where he took a stab at teaching a class, then as a comparison visited a charter school in New York City and retaught the same lesson. Watching footage of the New York City school, I was struck again by the sharp economic lines that are drawn between so many schools in our country and how in many those lines are strongly correlated with race.

Part of this post is to ask the same big question educators continue to grapple with, one that I am fairly certain we cannot solve in the education sector alone: why do we have a class system in our public schools?

The other part of this post is to raise an itchy question, one that won’t sit well with everyone that reads this, but one that I think we must face and can address within the education community: why, at times, do we feel it’s okay to teach “other people’s kids” differently than our “own”?

Why do we have a class system in our public schools?

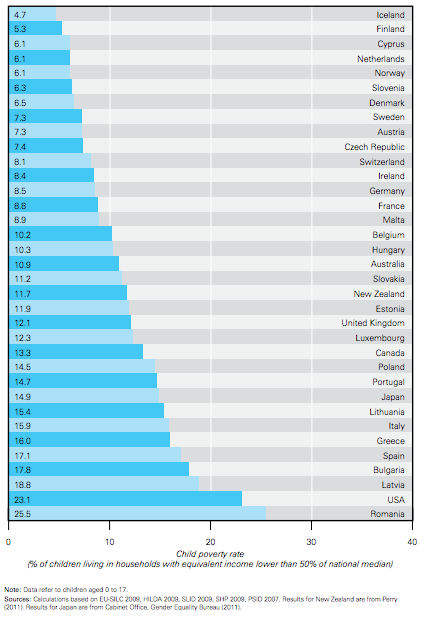

The Inside Man episode (to much the relief of many twitter viewers) brought up briefly the issue of child poverty in the United States, rightly pointing out that the US is has one of the largest child poverty rates of any developed country.

I would add that the US not only has an extremely high child poverty rate, but the gap between the official poverty line and what the average family living in poverty makes is the largest of the studied countries. (Note that Finland, which the show set as the answer to “America’s Education Failure,” has been near the top in both of these diagrams. A point the episode made as well.)

I, like I am sure you, see this play out in schools across the country in a startling way, where in many instances it is not that one school is deeply diverse in terms of income (some are, though they tend to be few), instead it is that schools become segregated within districts. Affluent students here, poor students there. Race, then too often, follows that trend.

The New York Times did a series of stellar pieces in May of 2012 on the ethnic divide in New York City schools, the first called “To Be Black at Stuyvesant High School” and the second “Why Don’t We Have Any White Kids?” which resonates the loudest because it is largely told through the perspectives of students attending majority-white or majority-black schools. And this corresponding infographic is worth the click, as it points out starkly that New York City schools are some of the most segregated in the large cities, though notice that segregation is not only a reality in New York.

Think of your own school. Now the one down the road. Now the one on the other side of town.

This is not new news. Jonathan Kozol wrote about the income divide and the racial divide in schools back in 1991 with Savage Inequalities. Yet, here we still are. Yet, every child’s life is of equal worth.

I also am not sure that this is an issue that the education sector alone can solve. I balk at the notion from some in the education reform movement that if schools were just “better” poverty would go away (see more on this in my post Education’s Own 47%). I do, though, think it’s one we need to continue to look at squarely in the eye and say out loud to anyone that will listen. It is not okay that in one district I can work with a school that has more technology, books, and supplies than it can possibly use and many of the children are white and largely middle and upper income. Then several miles away, in the same district, is a school with failing infrastructure, novice (though well intentioned) teachers, and many of the children are black and hispanic and largely lower-middle income or living below the poverty line. And I am not just talking about New York.

We need solutions, and we need everyone present at the table to make them. I would love to learn more for anyone who has pieces of solutions.

Why is it okay to teach “Other People’s Kids” differently?

Now the other part of this post.

I want to start off by saying that while I am aiming to raise issue with the practices that were portrayed on camera, I do not intend this to be complaining about just one school. I have seen practices, popular books, curricular materials, and even entire school cultures are designed in similar ways. I raise this one example to bring up many. Also, I do not take away from the well-meaning nature of the staff there or anywhere. You can see on the faces of the educators that this school was a place they were proud of, and I do believe they were doing the best they currently knew how to do without any intended malice.

One issue: the amount of time low-income schools spend testing.

This particular school prided itself on giving tests and collecting data all of the time. Truly, all-the-time. One scene showed an educator sliding Scantrons into a grading device and describing how it was important that they developed tests that really revealed what students knew and could do. While I do believe that gathering on-going data on students is useful, I also know that educators can learn to gather data in ways that do not leave students filling in bubbles continuously. Frankly, the better we get at studying students, reading their strengths and needs, the less we need to make dittos for them to fill out.

This then brought to mind the amount of “test prep” I see schools engaging in across the country and how in many instances I observe the most in schools with the lowest SES. On average, I’d estimate that those high income schools I mentioned earlier typically spend anywhere from only 2 weeks before a standardized test up to, at most, 20 minutes per week, on test preparation. Educators there worry about their jobs like everyone else, worry about their scores showing “growth,” yet their students often perform so well on those assessments that the level of panic is lower than average.

Alternatively, those low income schools? Entire units lasting one month or more, plus “Saturday Academy” several weeks out of the year, plus after school test-prep time, and often multiple periods per week spent drilling. I get that largely these schools are running scared to show higher scores and doing all they can. But I also ask, is this okay? Should our lower income, many times minority, students spend less time in authentic reading, writing, math, art, music, gym, play than their more affluent counterparts? Does that sit well with you?

The other issue: the belief in how students learn to “do school.”

I was also startled by, as were several twitter viewers, how this school relied so heavily on hand snapping, clapping, cold-calling, and other methods of “training” for teacher-student interactions (and actually how much Morgan, the outsider, loved it!). Here is a clip (forgive CNN’s advertising lead in).

While I admire that Doug Lemov spent years studying new and experienced teachers’ management and he uncovered many truly helpful and clear techniques for his book Teach Like a Champion, which this particular school was built around, I was also struck by the stale nature with which these techniques were delivered and the what to me appears to be the joylessness with which many of those students, in tucked in uniforms, clap-snapped their responses. I know, as the show pointed out, that many students excel in that school — and I am sure in others like it.

Again, they are good people trying their hardest. This is not necessarily a knock on silly dances, gestures, or management techniques, either. Tim, a 5th grade teacher at a school in Taiwan has a classroom chart of “claps” that they learn and make up together as the year goes on. It’s a hoot, it’s community building (I was partial to the “Paula Abdul”).

What this is a question of is, to be totally frank and probably not politically correct, would that scene fly in a majority white, upper middle class school? If not, how would those children be talked to, taught to act in the classroom, learn to “do school”?

It reminds me of a sit down with administrators at a small, largely low-income, school a few years ago. It had been my first day visiting the school. While the classrooms were light and bursting with a friendly atmosphere, in the hallways the otherwise lovely staff turned into drill sergeants, barking orders at students and at times even going beyond the point of disrespect. I sat in the office with the leadership team at the end of the day, during another passing period, and listened to the caustic yelling once again. I said, “You have so much going for you here, but I just need to say this, the hallway behavior by the teachers I find offensive. Why are they talking to the students like that?”

The first response was not what I expected, “Well, that’s what the other school we share this building with does and they must be doing something right, their scores are so high.”

I pressed on, “But, who cares about scores? Would you want your children spoken to like that?”

We talked a bit more, they were clearly not happy with me and my observation. Yet, two weeks later, the hallway drill sergeant personas had largely gone away. And have never come back.

I am a realist, pragmatic, have taught my own students, and now teach next to teachers in schools all over. I get that some students can be challenging, that we reach for solutions when we feel we aren’t doing things well enough by them. I also, however, think we need to step back often and reflect:

- am I giving these children the same dignity and respect that I ask in return?

- am I teaching them the way I want to be taught?

- am I teaching them compliance or independence?

- am I teaching these students differently than I would others?

- Why?

- Does this feel right to me?

- What can I change?

- Does this feel right to me?

- Why?

I, personally, aim to have the positive answer with each of these questions. But I also know I have not always. I certainly know more today than I did years ago, how to be instructionally effective while also giving respect to learners. Yet I know these are questions I much continually ask, because I do not always fit the image I want of myself.

We can always outgrow out best thinking and challenge our own assumptions. Our students need us to.

Thank you for all you do, and give, for your students and to those well beyond your doors.